The world of 'The Blackstone Key'

Coaching inns

Coaches were an important means of travel in the eighteenth century, and inns were built or expanded to accommodate the growing trade.

Even wealthy people who travelled in their own vehicles hired horses from 'posting houses'. These were establishments located at regular intervals on the main roads, where public stagecoaches and mail coaches stopped to pick up and discharge passengers and to obtain fresh horses. A busy inn might provide stabling for 50-60 post horses and an equal number of coach horses. Many also kept pairs of horses and chaises for local hire.

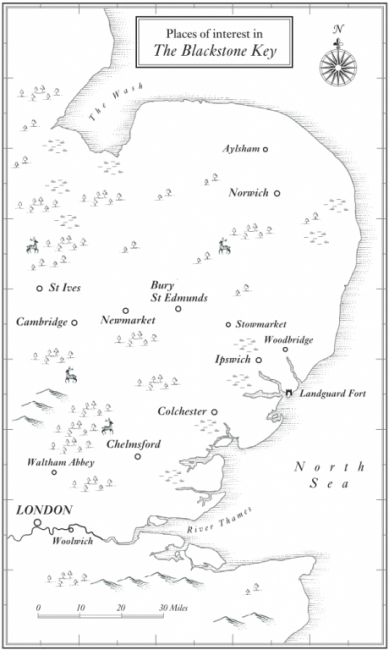

Mary Finch's journey to Woodbridge and Captain Holland's journey to London and Waltham Abbey in The Blackstone Key occur along well-established routes and feature popular inns of the time. Several are still in existence, including the Eagle in Cambridge, the Angel in Bury St Edmunds, and the Crown in Woodbridge. The Great White Horse Hotel in Ipswich entertained Lord Nelson and is mentioned in Dickens' Pickwick Papers.

Although delays and accidents were not infrequent – the result of bad weather, bad roads, reckless driving or some combination thereof – coaches aimed to provide a fast, efficient service. A stagecoach might average six and a half miles per hour, and a mail coach a speedy eight. Some vehicles travelled overnight, like the mail from Ipswich, which set off at 9:30 pm and arrived in London at 7:00 am, and brief stops for food might or might not be built into the timetable. One service between Bury and London boasted that it departed the capital at 5:00 am and reached its destination at 3:00 pm, thus avoiding 'the very tedious and disagreeable delay of dining upon the road.'

Experienced travellers like Mrs Oldworthy, who were also good cooks, did not have to choose between speed and sustenance.

Gunpowder production

One of the villains of The Blackstone Key, the treacherous Joseph Sault, is employed at the Royal Gunpowder Mills at Waltham Abbey.

Gunpowder production was largely a private industry at this time, but the Crown had purchased the Faversham Mills in Kent in 1759 and the Waltham Abbey facility in 1787. The government did not expect to produce all of the powder required for military purposes, but rather to guarantee a reliable product and set a standard through scientific methods of production. Henceforth, the powder-makers who wished to sell to the government – and most did – would have to show that their Large Grain powder could fire a ball as far as that produced at Faversham or Waltham Abbey.

Gunpowder production was centred in Surrey, Kent, Sussex, and Essex, and there were good reasons for this. These counties either produced or had easy access to the three ingredients of gunpowder: charcoal from local forests, and sulphur and saltpetre, which were shipped to London from Italy and India, respectively. Powder-makers in the southeast of England transported their wares along rivers such as the Lea, Darent, Crane, Mole, and Hogsmill, to storage facilities on the Thames, making inland boating quite a dangerous pastime.

Horse-racing at Newmarket

Horse-racing was extremely popular in the eighteenth century, and Newmarket was already famous as a centre of the sport.

In addition to its regularly scheduled race meetings, the Newmarket course hosted less conventional spectacles, among which the race that disrupts Mary Finch’s journey at the start of The Blackstone Key would not have stood out. Spectators came to see timed races, as when a horse attempted to run 23 miles in an hour, or a man attempted to ride 50 miles in two successive hours (both were successful), or dramatic, head-to-head contests.

In 1773 the race between Mr Blake’s Firetail and Mr Foley’s Pumpkin produced a spectacular result, with both horses completing the Rowley mile (actually a mile and 17 yards), in the remarkable time of one minute and four seconds.

Mr Somerville's dinner party

In the course of the dinner party at Woolthorpe Manor, Mr Somerville mentions the earlier visit of a French aristocrat to the area and his interest in Suffolk horses.

This was François de la Rochefoucauld, the son of the Duc de Liancourt, who undertook an English tour in 1784 with his younger brother and tutor. After spending a week in London they altered their itinerary in favour of East Anglia – possibly because of a favourable account of the weather, and possibly in order to be near the celebrated writer and economist, Arthur Young. They settled in Bury St Edmunds but also travelled more widely in Suffolk and Norfolk, and François wrote a lively, informative account of his experiences and of the region.

Happily, Mr Somerville’s fears for his safety were misplaced. Rochefoucauld survived the French Revolution and the wars that followed, and died in Paris in 1848.

Suffolk smugglers

Even before she arrives at White Ladies, Mary Finch is warned about smugglers or ‘free-traders’. Smuggling was common in Suffolk and across Britain during the eighteenth century, with tea, tobacco, silk, wine, and spirits being popular cargoes.

Smuggled goods would be brought ashore at secluded locations, cached, and then transported inland, typically to London. In some areas, obtaining and transporting the goods were separate operations, but some large, well-organised gangs managed the entire affair, relying upon fear or complicity among local residents to avoid detection, and employing violence against any who opposed them.

The ‘golden era’ of British smuggling came to an end in the 1780s, when the government cut the duties on tea and French wines, introduced a comprehensive warehousing scheme for tobacco, and passed legislation authorising the seizure of vessels ‘hovering’ within three miles of the English coasts and found to be carrying wine, tea, or coffee. These measures, along with the increased activity of the customs service and the willingness of juries to impose harsh penalties on convicted smugglers, severely stemmed, but did not cut off, the flow of illicit goods.

The trade continued in remote areas, and when war with France began in 1793, enterprising men on both sides of the Channel recognised the commercial opportunities that hostilities between their two countries presented.

The Woolwich Warren

Captain Robert Holland serves on the staff of the Royal Artillery regiment. The regimental headquarters was the Warren, the arsenal at Woolwich, which was then a village approximately nine miles from London.

Unlike the rest of the Army, the artillery was part of a separate branch of government – the Ordnance department – which bore responsibility for armaments and the men who employed them. It was fitting, therefore, that the arsenal should reflect both functions. Beginning with a purchase of some 30 acres by the Crown in 1671, the arsenal grew gradually to serve four related purposes: manufacture and storage of weaponry, research into new weapons and equipment, accommodation of the officers and men of the regiment, and practical instruction for artillery and engineer cadets.

The last, laudable aim of insuring that commissioned officers were competent in such subjects as mining, gunnery, sapping, and bridge-building sometimes had to give way to necessity. When the French war began in 1793, the demand for officers was so keen that the public passing-out exams were dispensed with in favour of an internal exam, and even this was stopped in 1795.

Captain Holland, of course, would have been subject to the more rigorous process of qualification.

White Ladies

The name of the Finch estate recalls the Cistercian monastic order, whose adherents were known as ‘White Monks’ and ‘White Ladies’ during the Middle Ages because of the colour of their habits.

Founded in 1198, the order stressed personal spirituality and an austere lifestyle, typically involving manual labour. The first English abbey was established in 1228. Female religious received little encouragement from the order, but ‘unofficial’ convents of women following Cistercian customs sprang up in England and Wales during the thirteenth century.

Although White Ladies is not modelled upon a particular establishment, its location on the Suffolk coast should come as no surprise. The Cistercians usually chose remote sites for their houses, and one of the few fully incorporated nunneries was actually founded at Marham, Norfolk in 1251. All monastic houses in England and Wales either surrendered to or were suppressed by the Crown during the sixteenth century, and many of them – like White Ladies – passed into private hands.