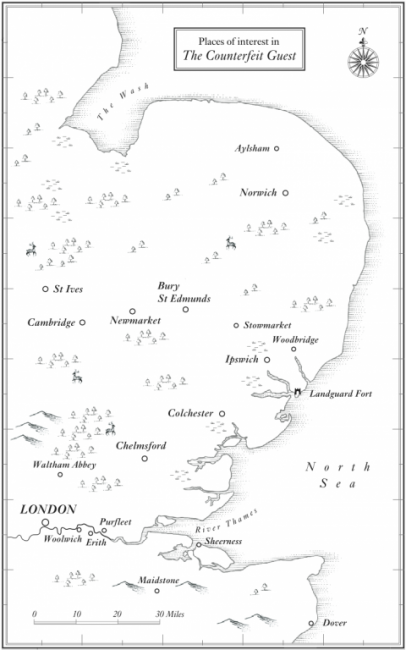

The world of 'The Counterfeit Guest'

Army and Navy Mutinies

Unrest among the Guards and artillery regiments in the spring of 1797 was quickly brought under control. The two naval mutinies were much more complex affairs, and of these, the mutiny at the Nore anchorage was the most serious. The Spithead mutiny broke out on 16 April. Following negotiations with the mutineers, the government agreed to a pay increase, better food, and a pardon. A royal proclamation confirmed the settlement on 21 April, and had not been for an administrative delay, the mutiny would probably have ended at that point. It did end on 15 May in a mood of general good humour, thanks partly to the esteem in which the men held Admiral Howe, who had been sent to Portsmouth with copies of the pardon and the newly enacted legislation. The Nore mutiny lasted from 12 May until 16 June, and was marked by the government’s unwillingness to negotiate, and by the more militant attitude of the mutineers, some of whom had French sympathies. Not only were convoys delayed for want of naval escorts, commercial traffic on the Thames was impeded, and London was threatened with a blockade. The government responded by withholding supplies from mutinous ships and removing navigation aids from the Thames. Legislation was hurriedly enacted to prevent the seduction of sailors away from their duty and to restrict contact with the ships in mutiny. On 6 June a royal proclamation declared the mutineers rebels and excluded the ringleaders from any pardon that might be forthcoming. When the mutiny finally collapsed, Richard Parker, the ‘president of the delegates’ was convicted of treason and hanged, and a number of other men were executed, flogged, or transported. The vast majority of those who had participated in the mutiny, however, simply returned to their duty, and helped to defeat the Dutch in the battle of Camperdown later that year.

Charles Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805) was the Master of the Ordinance at the time of the Woolwich mutiny. He is perhaps best known as the general commanding the British forces at Yorktown in 1781, whose surrender signalled the end of the American Revolution. Defeat, however, was rare for him. From 1785-1793 he was governor-general of India, during which time he introduced civil and military reforms and defeated Tippo Sultan in the Third Anglo-Mysore war. He almost returned to India in 1797, but instead was appointed lord lieutenant of Ireland the following year. There he oversaw the defeat of the rebellion of 1798 and helped to guide the Act of Union through the Irish parliament. In 1801, in the capacity of minister plenipotentiary in the Addington government, he signed the Peace of Amiens that ended, temporarily, the war with France.

Funerals

Funerals could be complex affairs in the late eighteenth century, although the rituals of grief, burial, and mourning were not as formally prescribed as in the nineteenth century. ‘Funeral arrangers’ or ‘furnishers’ managed the formal process for the upper and middle classes, with ‘undertakers’ performing this function at the lower end of the social scale. At the very least, proper provision had to be made for the body of the deceased. This could include an inner coffin, a lead shell, and an outer coffin of oak or mahogany. All three could be expensively decorated. The body usually remained at home until the day of the funeral, which might be 7-12 days after the death. Because embalming was unusual outside the aristocracy and royal family, coffins were sealed, and measures were taken to minimise the evidence of decay. The participation of women at funerals seems to have been varied in this period. Cassandra Austen did not attend her sister Jane’s funeral in 1817, but there are contemporary references to women mourners and even pall bearers in the 1780s and 90s. The pall was a cloth spread over the outer coffin when it was borne to the church and to the grave. Four ‘bearers’ held the corners, and where the deceased was a woman, her female friends might be chosen to perform this task.

Italian opera

The home of Italian opera in London during the eighteenth century was the King’s Theatre, Haymarket. Originally called the Queen’s Theatre, it was built in 1704 and presented approximately 60 nights of opera and ballet each season on Tuesdays and Saturday evenings. Attending the opera was a social as well as a musical experience. Visiting one’s friends in their box was a perfectly acceptable alternative to listening to the singers, and open spaces on either side of the pit were frequent places of assignation. Private conversations, rowdy behaviour, and even the presence of some patrons on stage could disrupt the performance. Actual criticism, when it was expressed, could take the form of hissing and the throwing of fruit. Paisiello’s Nina, however, was performed to much acclaim in the spring of 1797, the Oracle describing it as ‘unmatched in the magic power it has over the human breast, with respect to the tender simplicity, delicacy of expression, and pathetic effect.’

John MacLeod

John MacLeod (d. 1834) was deputy adjutant-general in the Royal Artillery in 1797, and was well known for his administrative efficiency, his kindly regard for the men under his command, and his tactful dealings with the often frustrating Ordinance Board. In 1809 he commanded the artillery in the Walcheren expedition, and in 1814 he was appointed colonel-commandant of the regiment and director-general at Woolwich. His son, Lt Col Charles MacLeod of the 43rd Foot, was killed leading the assault on the breach at Badajoz in April 1812.

Lincoln's Inn

Lincoln’s Inn is one of the four ‘inns of court’ – the others being Gray’s Inn, the Middle Temple, and the Inner Temple – institutions dating from the late Middle Ages that came to regulate the practice of English law. The inns began as places of accommodation for practitioners and students, but they soon assumed an educational function, with the senior members – called Benchers – providing lectures and presiding at ‘moots’ and other exercises in which students demonstrated their knowledge of legal argumentation. By the eighteenth century this function had largely ceased, but the inns retained the authority to call students to the bar, thereby designating them barristers-at-law and permitting them to practice as advocates in the English common law courts. Every barrister, therefore, was a member of an inn, and in this period most London barristers would have had rooms there or nearby. Sir John Scott was a member of the Middle Temple, but in the 1790s he had rooms in Lincoln’s Inn.

Mourning

A table of mourning regulations in France, published in 1765 prescribes a period of six months for parents, and one year and six weeks for a husband. Dress during mourning was also stipulated; for example, a widow should wear black wool for her ‘first mourning of six months, then black silk for a comparable period, which was designated as ‘second mourning’. During the final six weeks of ‘half mourning’ she should wear black and white. Women’s magazines of the 1790s described black satin and velvet as fashionable mourning fabrics. In wealthy establishments the servants as well as family members could go into mourning, and persons attending a funeral were expected to dress appropriately. Men often wore black cloaks, sashes, and hatbands, and women might wear black hoods.

Purfleet gunpowder magazine

The Royal Gunpowder Magazine at Purfleet was established by Act of Parliament in 1760, and much of the facility was built between 1763 and 1765. The magazine buildings were specially constructed to guard against sparks, facilitate ventilation, and limit the damage done in the event of an explosion. Safety practices were also employed. The civilian ‘powder men’ wore only the clothes and shoes provided; barrels were never rolled, but wheeled. As no artificial light was permitted inside the magazine buildings, polished copper plates were used to reflect sunshine from the open doors into dark corners when necessary. A garrison of artillery also protected the site. Purfleet stored as much as 52,000 barrels or 2,300 tons of gunpowder, and was the receiving house for all gunpowder manufactured or purchased by the government. This meant that shipments were coming into and out of Purfleet on a daily basis, and an accidental, but devastating explosion was a constant danger.

Sir John Scott

Sir John Scott (1751-1838) served as solicitor general and then attorney general from 1788 to 1799, and was later appointed lord chancellor. His tenure of that office (approximately 25 years in total) is the longest in history. As the Crown’s senior law officer, he drafted much of the anti-Republican legislation introduced in during the 1790s and undertook several high profile prosecutions for treason and seditious libel. He was certainly aware of government spies, although whether he had particular knowledge of the individuals and their activities is unclear. Politically conservative, he was also known for his extreme caution in legal matters. The latter tendency may have weakened him as a prosecutor, and undoubtedly contributed to the problem of ‘delays in Chancery’ that was satirised by Charles Dickens in Bleak House.

The British Museum

The British Museum was established by Act of Parliament in 1753 and was opened in 1759. Its first collections comprised books, manuscripts, and perhaps most importantly, the vast collection of Sir Hans Sloane, whose bequest of biological, botanical, and ethnological specimens, antiquities, books, and prints had prompted the museum’s creation. Other notable acquisitions during the eighteenth century included Sir William Hamilton’s classical antiquities, objects from the South Seas donated by Captain Cook, and the first Egyptian mummies, courtesy of William and Pitt Lethieullier. From the beginning, members of the public were admitted to the museum, free of charge, but only after their application had been accepted. A member of staff would then take them round the museum. The process of scrutiny and issuance of tickets could take several weeks, and some visitors complained that their eventual visit was hurried and uninformative. A private tour conducted by one of the trustees, therefore, would have been a privilege enjoyed by few, and it is to be lamented that Captain Holland did not fully appreciate this.

The London Season

At least from the 1730s and 40s, wealthy Englishmen and women spent part of each year in London and part in the country or travelling abroad. Their movements reflected the weather, the activities of the Court, and the dates of parliamentary sessions. As all three of these were changeable, so were the movements of ‘fashionable world’. In general, however, a short London ‘Season’ occurred between late January and the Easter parliamentary recess, the highlights of which would be the opening of the opera and the first royal levee. When Parliament reassembled after Easter and the first royal drawing-room was held, the true Season would begin. This would last until Parliament was prorogued in June, after which many people would drift away. Some would return for the autumn parliamentary session, but others would remain in the country until after Christmas.

The Woolwich Warren

Captain Robert Holland serves on the staff of the Royal Artillery regiment. The regimental headquarters was the Warren, the arsenal at Woolwich, which was then a village approximately nine miles from London.

Unlike the rest of the Army, the artillery was part of a separate branch of government – the Ordnance department – which bore responsibility for armaments and the men who employed them. It was fitting, therefore, that the arsenal should reflect both functions. Beginning with a purchase of some 30 acres by the Crown in 1671, the arsenal grew gradually to serve four related purposes: manufacture and storage of weaponry, research into new weapons and equipment, accommodation of the officers and men of the regiment, and practical instruction for artillery and engineer cadets.

The last, laudable aim of insuring that commissioned officers were competent in such subjects as mining, gunnery, sapping, and bridge-building sometimes had to give way to necessity. When the French war began in 1793, the demand for officers was so keen that the public passing-out exams were dispensed with in favour of an internal exam, and even this was stopped in 1795.

Captain Holland, of course, would have been subject to the more rigorous process of qualification.

Three Mariners

The Three Mariners tavern in Lambeth is among the main Thames stairs and docks listed on John Rocque’s 1746 map of London. Whatever its reputation in the eighteenth century, the tavern seems to have been a popular haunt in the seventeenth century. Samuel Pepys writes of visiting in 1661 for his morning draught of ale, ‘and staid awhile very merry’. While conducting repairs in 1752, the landlord found a large, elegant armchair, believed to have been used by Charles I when he visited the Three Mariners ‘on his water tours with his ladies, … to play at chess, &c.’

White Ladies

The name of the Finch estate recalls the Cistercian monastic order, whose adherents were known as ‘White Monks’ and ‘White Ladies’ during the Middle Ages because of the colour of their habits.

Founded in 1198, the order stressed personal spirituality and an austere lifestyle, typically involving manual labour. The first English abbey was established in 1228. Female religious received little encouragement from the order, but ‘unofficial’ convents of women following Cistercian customs sprang up in England and Wales during the thirteenth century.

Although White Ladies is not modelled upon a particular establishment, its location on the Suffolk coast should come as no surprise. The Cistercians usually chose remote sites for their houses, and one of the few fully incorporated nunneries was actually founded at Marham, Norfolk in 1251. All monastic houses in England and Wales either surrendered to or were suppressed by the Crown during the sixteenth century, and many of them – like White Ladies – passed into private hands.

William Congreve

William Congreve (d.1814) was the newly appointed commandant of the Woolwich arsenal in May 1797, having previously held the posts of superintendent of military machines and comptroller of the Woolwich laboratory. Congreve is credited with various improvements to gunpowder production and gun carriage design. He was an early advocate of government manufacture of powder, and urged William Pitt to purchase the Waltham Abbey mills in 1787. Congreve’s son, also named William, invented the Congreve rocket, whose ‘red glare’ is mentioned in the American national anthem.